There is quite a different sense of composition in this photo compared to the others shown so far. In 1971, I bought a Praktica Nova single lens reflex camera for $65 and began to take photography a bit more seriously. No more square photos.

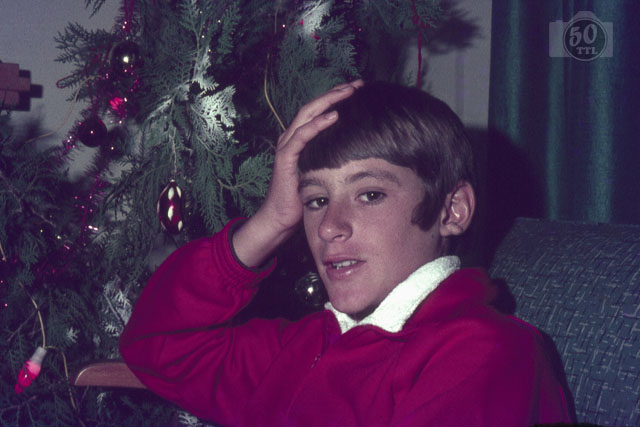

This photo, of my youngest brother, is the first colour photo I can identify that I took with the new camera. It’s not perfect. There’s a bit too much of the chair. His eyes are just off the intersection of thirds that would make it a more satisfying composition. However, the parallax error is gone. Now I was truly seeing photos through the lens that took them.

The sense of composition is even stronger in this photo of my other younger brother. I am pleased to see that I took a low angle on the shot to eliminate clutter and show an expansive sky, which is quite fitting for the subject matter.

The Praktica came with a f2.8 50mm Tessar lens. It was a fully manual camera, with no exposure meter. Exposure was a bit hit and miss at first, guided only by the exposure suggestions printed on the side of film packaging.

I soon bought a Jonan Elmat light meter, which was a handheld device about the size of a mobile phone. You had two choices: You could stand where you were going to shoot from and measure the light being reflected back to the camera, or you could stand where the subject was and measure the light falling on whatever you were photographing. I quickly learned how to adjust camera settings and manipulate the relationship between aperture and shutter speed. Automatic cameras do this invisibly. At least, it’s invisible until something goes wrong, and then the limitations of the camera’s automation can be horribly visible in a blurred, dull or featureless photo.

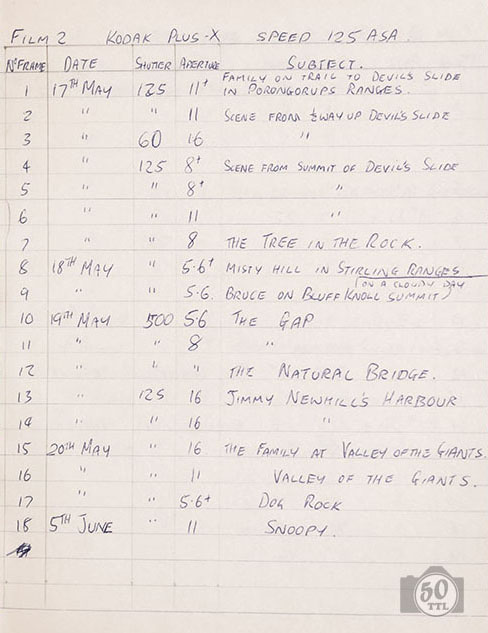

By May 6 that year, I was processing and printing black and white film. I ruled up pages on an exercise book and started writing down details of the photos I took and the camera settings I used. These days, digital cameras record this information automatically as the photo metadata, and you can check it out in photo editing programs: shutter speed, aperture, ISO settings, zoom length, flash settings and so on.

You can refer to the metadata to improve your technique by relating flaws in the photo to the settings you used at the time. This photo would be better with a shallow depth of field – what aperture did I use? This photo is a little blurred – what was the shutter speed? This photo is too noisy – what was the ISO?

Not so easy in 1971. So here is metadata 1971-style: Manual, like the camera. Of course, I had to use up a whole roll of film and get it processed, or do it myself, before I could see the consequences of my camera settings. Once I had the images available to me, I looked back at my ‘metadata’ to see if I could learn any lessons to help me take a better photo next time.

This page lists the photos I took on a family holiday in the Great Southern in May 1971. Remember when the school year had three terms and the holidays were in May and September? We obviously drove from Perth and visited Porongurup (which I now know how to spell), the Stirling Range, Valley of the Giants and some of Albany’s standard tourist spots. Note how the shutter speed goes up to 1/500th and the aperture to f5.6 at The Gap, where I was probably trying to freeze the motion of the spray, but down to 1/125th and f11 or 1/60th and f16 in the Porongurups where I wanted more depth of field.

Eventually, I let the photo record lapse as study got in the way. I do not have 50 years of hand-recorded metadata available to me. However, the simple records I kept for a couple of years in an exercise book helped me to learn skills that have stayed with me for decades.